Contents • Part 1: In Russia • Part 2: In England • Blake set to music

Part 2: In England

1

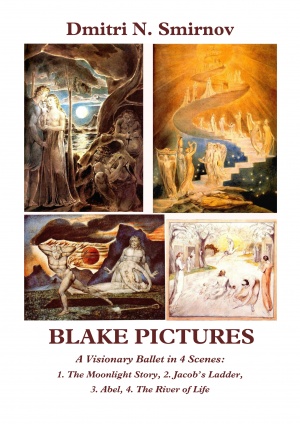

England welcomed us cordially in 1991. Our concert was a success: my Jacob’s Ladder, a musical depiction of William Blake’s magnificent Jacob’s Dream of almost two hundred years before, came from Moscow to London to be played by the London Sinfonietta under the baton of a Russian conductor. It seemed to me that Londoners appreciated this. The horn concerto by my wife, Elena, was equally well received. After the concert we were invited to the Garrick Club, and together with our small children had a joyful dinner until late at night. The next morning we moved from Kensington’s Tara Hotel; our friends took great care of us and took turns in kindly offering us temporary shelter. The newspaper reviews were positive: “Its spiralling motifs and sun-lit instrumental colours [made] a dreamlike counterpart to the visionary William Blake picture which inspired it”; “Inspired by William Blake’s drawing of the Biblical story, this beautifully crafted piece is sectional, with contrasted instrumental groupings marking the boundaries. It is also refined, revealing sensitivity for instrumental characteristics and a predilection for lyrical phrases. The ending, when the first violin emerges from a lovely texture of celesta, vibraphone, bells and the higher stringed instruments is a moment of transcendent magic. It also exemplifies the economy of Smirnov’s writing: not a note was inessential.”[1] Our publishers were pleased and decided to print both our scores.

Soon Kathleen Raine (illus. 1) invited all of us for a cup of tea. The tea party lasted more than three hours, and we had a long and wonderful talk about Blake. I told her about my two operas based on Blake’s early prophetic poems and asked for advice about what to choose for my next Blake project. With no hesitation she showed me Blake’s illustrations for the Book of Job, which decorated the walls above her staircase, and said that they would be wonderful subjects for a dramatic musical work. As a present she gave me a few of her books about Blake, as well as her own Selected Poems and Autobiographies. She also gave us an excellent referral to her friend John Lane, an artist and head of the Dartington Hall Trust. She added, “He is crazy about William Blake exactly like we are, and he will definitely help you.”

My first composition written in England was a song cycle: Short Poems, op. 60, setting five lyrical miniatures by Kathleen Raine, in every line of which I have found echoes of William Blake:

|

I completed the work on 10 May and presented a copy of my manuscript to the poet during our next meeting in her little house in Chelsea. She was delighted and asked me to send her a recording when it was performed.

At the beginning of June I received a commission from the Composers’ Ensemble to write a piece for soprano and five instruments (two clarinets, viola, cello and double bass). I decided that it was a good opportunity set to music Blake’s "Silent, silent night," which was described by Thomas Mann in his Doctor Faustus, the story of the fictitious composer Adrian Leverkühn:

- At the time when I [Serenus Zeitblom] moved to Freising, Adrian was busy with the composition of some songs and lieder, German and foreign, or rather, English. In the first place he had gone back to William Blake and set to music a very strange poem of this favourite author of his. “Silent, Silent Night,” in four stanzas of three lines each, the last stanza of which dismayingly enough runs:

|

- These darkly shocking verses the composer had set to very simple harmonies, which in relation to the tone-language of the whole had a “falser,” more heart-rent, uncanny effect than the most daring harmonic tensions, and made one actually experience the common chord growing monstrous.[2]

When I finished this work and reread the episode above I felt as if Mann had been writing this about me and my new composition (illus. 2).

After the beautiful performance of this song by the soprano Mary Wiegold and the ensemble conducted by John Woolrich on 20 July 1991 at the Cheltenham Festival, I added two more songs—“The Tyger” (Songs of Experience) and “To See a World in a Grain of Sand” (“Auguries of Innocence,” Pickering Manuscript)—and entitled the work Three Blake Songs for voice and chamber ensemble, op. 61. Nine years later I created a new version of the cycle, Four Blake Songs for soprano and string quartet, op. 61a, by adding one more song, “A Divine Image” (Songs of Experience), borrowed from my opera Tiriel.

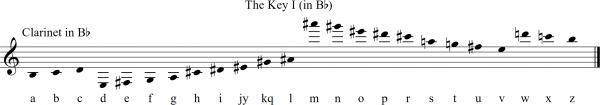

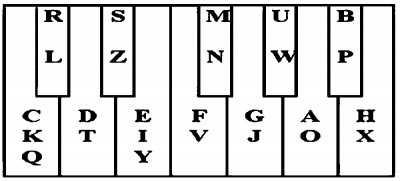

Almost every week my family and I moved from one friend’s house to another; we had already changed places in London ten times before Barry Gavin, a TV film director, suggested we stay at his cottage in the village of Cwm in Shropshire, where we happily spent the whole of July. I thought about Kathleen Raine’s suggestion that I follow Blake’s illustrations for the Book of Job to create some dramatic musical work. After looking at Blake’s engravings I chose four of them, using the captions above or below each of the designs as the texts for narration: 1. “There Was a Man in the Land of Uz” (Job 1.1-2), 2. “The Fire of God Is Fallen from Heaven” (1.16), 3. “Let the Day Perish Wherein I Was Born” (3.3), 4. “Then the Lord Answered Job out of the Whirlwind” (38.1-2). I decided to limit myself to a solo instrument, the clarinet, using the player as also a narrator; the player/narrator reads the text, then plays the melodic phrases representing the same words, translated into notes by a coding system where each letter corresponds to a certain note (illus. 3; for the code turned into music, see illus. 4).

This quite unusual and experimental opus, Four Studies after the Book of Job (Job’s Studies), op. 62, premiered on 25 October 1991 at Ohio State University. It was magnificently delivered by the clarinetist Bruce Curlette and sounded akin to a strange mysterious ritual, a sort of sermon in music.

Meanwhile I received a message from Devon: John Lane invited us to Dartington Hall on 8 August to discuss how he

could help us. This coincided with the second performance

of my “Silent, Silent Night,” which took place at the Dartington Summer Music Festival. Before our meeting my

family and I walked around the beautiful garden and suddenly found a big stone tablet with a carved, gold-plated inscription (illus. 5):

|

It made me feel that this place would be hospitable to us.

I told John about our discovery, and he answered that he was responsible for this tablet and the inscription. He asked his secretary to take our children for a long walk, then, after two hours of exciting conversation mainly focused on our mutual interest in Blake, declared that he had decided to provide us with a spacious six-room house for one year, beginning the next April—we had only to cover our gas and electricity bills. He drove us to our future house and around all the attractions in the neighborhood. All this seemed miraculous and we felt on top of the world. Later, when we told our friends about this, they exclaimed, “This is Blake smiling on you.”

This was followed by other news: on 19 August in Moscow there was a coup d’état, which made our return there precarious. Our British visas were already drawing to a close, however, and something had to be done. Our new friend Chris Tew wrote to Parliament, to the Chief Secretary to the Treasury David Mellor, with a request to extend our visas, and in early September there came the answer that we were allowed to stay indefinitely. At the same time, we received visas for a trip to music festivals in the USA and Germany, where our works were to be performed. We rented a house at 4 Geraldine Road, Chiswick, and there our children first went to school. I received new commissions from the London Sinfonietta and from the Chameleon Ensemble, both of which were directly related to Blake. One day in October we had a visit from a newspaper correspondent, who asked us a few questions. A couple of days later on the front page of the Independent a large picture of our family with an article by Norman Lebrecht appeared: “Russia’s Top Two Composers Flee to UK. The Smirnovs: Economic Migrants—or a Brilliant Musical Catch?” Lebrecht didn’t write exclusively about us but about all our colleagues who had fled Russia, an exodus that he described as “the most devastating musical migration since Hitler purged German culture in the 1930s.”

On 12 October, together with our children, we flew to America. We spent a week in Indianapolis, Indiana, and then moved to Columbus, Ohio, where four works from my Blake list were being performed: Job’s Studies, The Moonlight Story, The Seasons for soprano and ensemble, and the First Symphony, which was played by the Columbus Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Gunther Schuller. At the same time the symphony was also performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Oliver Knussen at the Royal Festival Hall in London, and it was a pity that I was unable to be in two places at once to attend both the Ohio and British premieres. From the USA we flew to the festival in Heidelberg, Germany, and on 4 November we returned to London.

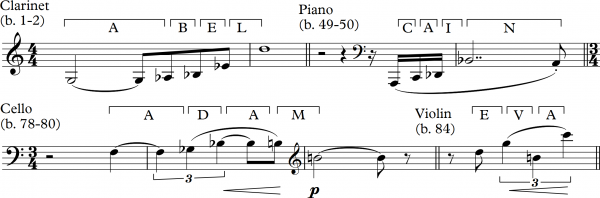

Deciding to continue my visionary ballet Blake Pictures, I focused now on Blake’s ink and tempera painting The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, which made a great impression on me when I saw it at the Tate. On 4 December I completed my new score: Abel for clarinet, violin, cello, and piano, op. 65. The four figures in the picture correspond to the four instruments: Abel the clarinet, Eve the violin, Adam the cello, and Cain the piano. In this work I used the musical alphabet (see illus. 9 in part 1 of the article) that I had invented in 1988. Each of the characters was given a unique motif, enabling me to attempt to grasp the spirit of the picture in musical sounds and shapes (illus. 6). The first performance took place on 24 June 1992 at St. Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, Orkney, played by the Chameleon Ensemble.

The 1st performance of this work took place on the 24th of June, 1992 at St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, Orkney, played by the Chameleon ensemble .

The next work was completed on 2 February 1992 in Cambridge, where we received a fellowship and three months' living allowance at St John’s College. This was The River of Life, for a chamber ensemble of 16 players, Op. 66. (illus 7).

It was inspired by the beautiful watercolor of the same title, which I had enjoyed viewing at the Tate; Blake illustrated the opening passage of chapter 22 of Revelation, enriching it with some additional details. Once he is known to have said, “The Last Judgment is one of these Stupendous Visions. I have represented it as I saw it.” Now I could say similarly that I had represented it as I heard it. The River of Life was first performed on 8 November 1992 at Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, by the London Sinfonietta conducted by Oliver Knussen. This became the fourth and last part of my imaginary ballet Blake Pictures (illus. 8). I call it “imaginary” because the ballet exists only in my own imagination. Although each of its four parts has been performed as a chamber ensemble work on numerous occasions, they have never been played together or staged as a ballet.

After three wonderful months in Cambridge and a short visit to Moscow, on 14 April 1992 we moved into our new house on the Dartington Hall estate. We spent the happiest nine months in that beautiful place, which looked like a paradise garden. Among six compositions that I wrote in that period, two had a Blake connection. I was reading the poem Vala, or The Four Zoas when the German organ player Friedemann Herz asked me to compose a short piece for solo organ. I immediately thought about Los and Enitharmon, two key characters in the immense cosmos of Blake’s mythology: Los, the Prophet of Eternity, symbol of poetry and creative imagination, and Enitharmon, the spiritual beauty, his consort and inspiration, whom Blake identified with himself and his wife, Catherine. In some respects I also began to identify them with myself and Elena. I composed Diptych, op. 70 (illus. 8), in two movements—Los and Enitharmon—based on the melodic forms extracted from the letters of their names. Herz premiered it on 25 September 1992 at Riga Dome Cathedral, Latvia.

Right: Diptych (Los and Enitharmon) (St. Albans: Meladina Press, 2002).

Another work written at Dartington was a Piano Quintet for piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass, op. 72, dedicated to the memory of my teacher, the composer Nikolai Sidelnikov. A special principle of pitch organization that I found for the second movement, which was influenced by Blake’s poem “The Crystal Cabinet” (see also op. 27g in part 1 of the article), became the basis for the whole cycle, unifying all three movements. The first performance took place on 23 January 1993 at the Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester, played by the Music Group of Manchester. The Quintet was also recorded on CD on the Meridian label (CDE84586) by the Primrose Piano Quartet and Leon Bosch, double bass.

Very soon, rather unexpectedly, Elena and I received a five year contract as visiting professors of composition at the University of Keele in Staffordshire. In January 1993 we moved to the campus, where we had a free house and a spacious room in the university building where I taught and composed music. In the first year, the staff and students of the Music Department presented me with a magnificent gift: secretly they prepared a production of my chamber opera The Lamentations of Thel and told me about it when everything was ready. The performance, with costumes and even scenery, was on 29 May. It was conducted by Rahmil Fishman, and the role of Thel was sung by Jane W. Davidson, the same singer who participated in the premiere of the opera in 1989. This time she was also the stage director.

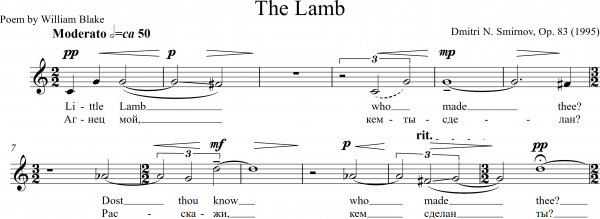

These five years were an incredibly productive period, during which I wrote more than forty compositions. The most ambitious was 'The Guardians of Space, an almost half-hour orchestral suite in eight movements, op. 79, 1994. It was an expanded orchestral version of my piano cycle The Seven Angels of William Blake, op. 50. Another piece was The Lamb for countertenor and six viols, op. 83 (illus. 9), a setting of Blake’s poem from Songs of Innocence, which was first performed on 2 May 1995 at the Purcell Room in London by Michael Chance, countertenor, and the ensemble Fretwork.

One more piece, Miss Gittipin’s Talk for soprano solo, op. 98 (illus. 10), was the setting of a prose fragment from An Island in the Moon. It has been performed only once, by the wonderful singer Jane Manning in a workshop in front of the students of the Music Department. I was very much attracted to Blake’s witty satiric burlesque and even thought of writing a comic opera on the subject, but, because the author left it unfinished, I couldn’t manage to produce a good libretto with a convincing conclusion.

In autumn 1998 our university contract came to an end and we moved to St. Albans, nearer to London, where we live now. Here I have written more than eighty compositions, more than ten of which are associated with Blake. The first was A Cradle Song, from Songs of Innocence, for soprano and piano, op. 126, 2001. It was followed by the electroacoustic work Innocence of Experience for tape, op. 132, 2001, quite a long cycle, lasting 27 minutes. It includes six Innocence songs—“Introduction,” “The Lamb,” “Laughing Song,” “Infant Joy,” “A Dream,” “The Divine Image”—and four from Experience—“The Clod & the Pebble,” “The Sick Rose,” “The Fly,” “The Tyger.” Five of these poems I had already set to music previously, and now I returned to the musical material of those settings, but presented it here in a quite different manner. First I asked my daughter to read the poems and worked on the recording of her voice in my home studio, editing it and adding to it some sounds of nature, musical instruments, and so on. For “The Sick Rose” (no. 8), for example, I found a completely new musical idea, representing the rose with a three-part contrapuntal chorus played by the electronic synthesizer, which imitated string instruments, and the worm with a single snake-like voice using the same notes dispersed by wide intervals in the very low register (illus. 11).

The next work on a Blakean subject was the Inferno (Eighth String Quartet) in seventeen episodes, for two violins, viola, and cello, op. 152, 2008, the first part of our family project, a cycle of three string quartets after Dante’s Divine Comedy. It was commissioned by the Rodewald Concert Society in partnership with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. The second part, Purgatorio, was written by Elena, and the third, Paradiso, by our daughter, Alissa Firsova; our son, Philip Firsov, created three large ink drawings and later three engravings on the same subjects, which accompanied many performances of our quartets. While composing the Inferno I looked through the set of Blake’s 'Dante illustrations, and my music was greatly inspired by them, so I added to the score as a subtitle, “After Blake’s illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy.” Philip was also very familiar with these illustrations and in his work deliberately echoed some of Blake’s images, as can clearly be seen, for example, on the following detail of his drawing (illus. 12).

I can explain how the text of Dante’s poem and Blake’s images were reflected in my music. In Inferno canto 13 there is an impressive episode when the travelers, after having crossed the Phlegethon, enter the Wood of the Suicides (in the seventh circle, second ring). There is a loud groan from everywhere, as if whole crowds surround them, but no one is visible; when Dante, at the instigation of Virgil, breaks a branch, the tree cries, “Perché mi scerpi?” (Why do you scratch me?) (canto 13, line 36). It’s become clear: the suicides were turned into trees. Blake remarkably reflected

this in his illustration, where in the trunks you can see the features of human bodies.

In a certain sense, this idea is reflected in the very structure of the music: the listener hears separate sounds, melodic phrases, and chords, but in them are hidden real people, or rather their names, which are encrypted in the music. For this I used a simple musical alphabet that I had invented in 1997 (illus. 13).

Such a technique is now commonly called music cryptography (or cryptophony). For example, the fifth episode of my Inferno quartet corresponds to canto 4, Limbo, where Dante speaks about those who lived before the Christian era. In eight chords in bars 68-70 (illus. 14) it is possible to see that each of the chords is made up of the letters of the name (in Italian) of one of these characters: Homer, Horace, Ovid, Lucan, Elektra, Hector, Aeneas, and Caesar (read vertically). The first performance of the Divine Comedy cycle took place on 4 November 2008 at St. George’s Concert Hall, Lime Street, Liverpool; the performers were the members of the Dante Quartet.

The first performance of the cycle Divine Comedy took place on the 4th November, 2008 at St George's Concert Hall, Lime Street, Liverpool; the performers were the members of Dante String Quartet.

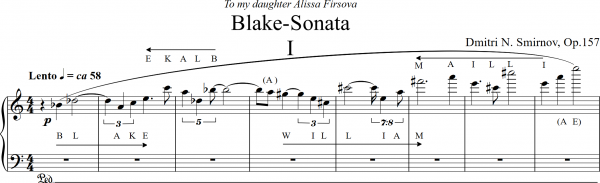

A similar principle was used in my Blake-Sonata (Sixth Piano Sonata) in two movements, op. 157, 2008, where I wanted to create a spiritual portrait of Blake by musical means. The first, slow movement is a set of variations on a theme based on the letters of Blake’s name transformed into music (illus. 15).'

The opening theme is also repeated at the very end of the sonata. The second, fast movement has the features of rondo-sonata form, and is a musical depiction of the poem “The Tyger”: its mirror symmetrical patterns represent the “fearful symmetry” of the beast. The sonata is dedicated to Alissa, who first performed it on 20 November 2008 at Deptford Town Hall of Goldsmiths, University of London. She also recorded it on her debut CD, Russian Émigrés (Vivat 109). The score was printed in the Meladina Music Series (illus. 16).

Right: Blake-Sonata (Sixth Piano Sonata) (Meladina Music, CreateSpace for Amazon.com, 2017).

My next Blake project was devoted to his so called “Visionary heads”: a series of black chalk and pencil drawings that he produced after 1818 for John Varley, astrologer. I was very much involved to the pre-compositional research, and created also an extensive article on this subject for English and Russian Wikipedia. Then I had chosen five of the drawings and composed a piano cycle titled the Visionary Heads, Op. 172, 2013, where I used the same technique as in two previous works. The cycle consists in five movements: 1. Blake's Instructor, 2. The Man Who Built the Pyramids, 3. Corinna, 4. Cancer Constellation, and 5. Owen Glendower. It was first publically played by my daughter Alissa Firsova on the 29th of March, 2014, at St Saviour’s Church in St Albans .

In 2013 I began compose a series of vocal miniatures after the Proverbs of Hell from Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. In December 2017 I have completed 20 of them, which formed all together the four notebooks with solo piano introduction to each of them:

1st Notebook, op151 (2006-07) Introduction 1. A Little Flower (56. To create a little flower is the labour of ages.) 2. The Busy Bee (11. The busy bee has no time for sorrow.) 3. An Eagle (54. When thou seest an Eagle, thou seest a portion of Genius. lift up thy head!) 4. The Clock (12. The hours of folly are measur’d by the clock, but of wisdom: no clock can measure.) 5. Pestilence (5. He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.) 6. Black and White (63. The crow wish’d every thing was black, the owl, that every thing was white.) 7. Eternity (10. Eternity is in love with the productions of time.)

2nd Notebook, op185 (2015-16) Introduction 8. Learn, Teach, Enjoy (1. In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy.) 9. The Cart and the Plough (2. Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.) 10. The Palace of Wisdom (3. The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.) 11. Prudence and Incapacity (4. Prudence is a rich ugly old maid courted by Incapacity.) 12. The Worm and the Plough (6. The cut worm forgives the plow.)

3rd Notebook, op186 (2016) Introduction 13. Dip him... (7. Dip him in the river who loves water.) 14. A fool sees not... (8. A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.) 15. He whose face... (9. He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star.) 16. No bird soars... (15. No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings.)

4th Notebook, op191 (2017) Introduction 17. All Wholsome Food... (13. All wholsom[e] food is caught without a net or a trap.) 18. In a Year of Dearth... (14. Bring out number weight & measure in a year of dearth.) 19. Revenges not Injuries... (16. A dead body revenges not injuries.) 20. The most sublime act... (17. The most sublime act is to set another before you.)

The score is printed in USA and available on Amazon :

In November 2017 I received quite unusual request from the Ensemble of the Soloists of the Georgian Symphony Orchestra to write a piece that could be played instead of Adagio of J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No.3. In fact that Adagio consists just of two short chords and only provides a link between two fast movements. I was happy to make possible to connect in one performance two great B’s: Bach and Blake, and composed “Blake Intermezzo” for string septet on the theme that is based on the letters of Blake’s name that I already explored in my “Blake Sonata”. I dedicated the piece to 260th Blake’s anniversary. The premiere took place in Tbilisi a few days later on 28th of November exactly on birthday of William Blake .

Later I made another version of the “Blake Intermezzo”, for double bass and piano, Op. 190a, 2017, on request of Javad Javadzade, a double bass player from the same ensemble .

The scores of the both pieces were published by SMP Press, USA .

So far the list of my Blake set to music contains 44 compositions written for the period of 38 years (between 1979 and 2017). In parallel with this I devote all my spare time to studying Blake and translating of his works into Russian. Publishing my work, I use pen names: Dmitri N. Smirnov for music and D. Smirnov-Sadovsky for literary writings. In 2016 I completed a book called “Blake”, his first full-length Russian biography. The book was published in USA, but in 2017 it was also published in Russia by Magreb.org Publishers.

Also I began a publication of a complete Blake’s works in twelve volumes in a bilingual format with my own Russian translations, and already issued first four volumes:

I am working now on the fifth volume of Complete Blake’s Works with eight “minor prophecies” that include some Blake’s poems that never been translated into Russian before, such as The [First] Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los. My another project, the first Russian translation of a poem “Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion” is already completed and is going to be printed soon by Magreb.org Publishers in Moscow.

I have been asked in many occasions: “Why are you fascinated by Blake? Why he is so important for you? What do you like about his work?” I can say that his works and ideas give me a strongest stimulus for composing music. His creative imagination and energy were so great that even now they able to inspire more than the works of any other poet, writer, thinker or artist. Some people say that his works are too simple and even naïve. But if it is so, together with this they contain an incredible power, depth and multitude of meanings. Some others regard his works too puzzling and incomprehensible. However this is what makes them so attractive, forcing us think and submerge into them to realize their deep meaning. He was and remains unique and original in everything he did, and I’m interested equally in his poetry and prose, visual art and philosophy. So, Blake became one of my main spiritual teachers, along with many others such as Dante and Basho, Hölderlin and Coleridge, Pushkin and Mandelstam, Bach and Beethoven, Mahler and Webern, Leonardo and Chagall: all of them seriously influenced my music and even my life, but Blake – more than anybody else.

1st of August 2017, St Albans, England

(Revised on 18th of March 2018)

Notes