Tiriel (libretto): различия между версиями

| Строка 28: | Строка 28: | ||

'''Cast''' | '''Cast''' | ||

| − | TIRIEL, old blind | + | TIRIEL, old blind king — baritone |

| − | HAR, his | + | HAR, his father — tenor |

| − | HEVA, his | + | HEVA, his mother — soprano |

| − | IJIM, his | + | IJIM, his brother — tenor |

| − | ZAZEL, his | + | ZAZEL, his brother — bass |

| − | HELA, his | + | HELA, his daughter — soprano |

| − | MNETHA, nurse of Har and | + | MNETHA, nurse of Har and Heva — contralto |

| − | MYRATHANA, the wife of | + | MYRATHANA, the wife of Tiriel — super |

| − | SONS OF TIRIELS (and daughters ad lib.) | + | SONS OF TIRIELS (and daughters ad lib.) — men’s (or mixed) choir |

| − | SONS OF | + | SONS OF ZAZEL — men’s choir |

| − | NIGHTINGALE, TIGER, BIRDS, | + | NIGHTINGALE, TIGER, BIRDS, FLOWERS — dancers |

''The action takes place at the beginning of human history.'' | ''The action takes place at the beginning of human history.'' | ||

| Строка 70: | Строка 70: | ||

TIR: Serpents not sons, wreathing around the bones of Tiriel! | TIR: Serpents not sons, wreathing around the bones of Tiriel! | ||

| − | Ye worms of death, feasting upon your aged parent’s flesh! | + | Ye worms of death, feasting upon your aged parent’s flesh! |

[O] listen! and hear your mother’s groans. No more accursed Sons | [O] listen! and hear your mother’s groans. No more accursed Sons | ||

She bears; she groans not at the birth of Heuxos or Yuva. | She bears; she groans not at the birth of Heuxos or Yuva. | ||

| Строка 98: | Строка 98: | ||

No! your remembrance shall perish; for when your carcases | No! your remembrance shall perish; for when your carcases | ||

Lie stinking on the earth, the buriers shall arise from the East, | Lie stinking on the earth, the buriers shall arise from the East, | ||

| − | And not a bone of all the sons of Tiriel remain! | + | And not a bone of all the sons of Tiriel remain! |

''Tiriel exit. Curtain down'' | ''Tiriel exit. Curtain down'' | ||

| − | + | ||

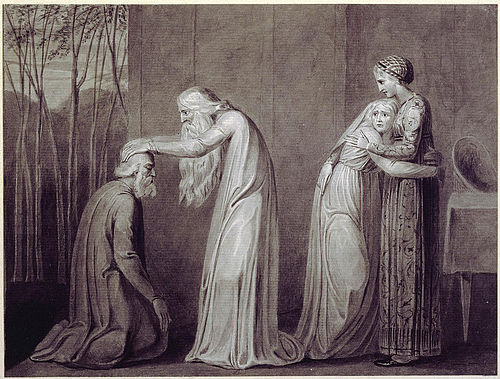

[[File:Tiriel plate2.jpg|500px|center]] | [[File:Tiriel plate2.jpg|500px|center]] | ||

<center>'' Har and Heva Bathing ''</center> | <center>'' Har and Heva Bathing ''</center> | ||

| Строка 140: | Строка 140: | ||

''(Heva descends from the cloud)'' | ''(Heva descends from the cloud)'' | ||

| − | HAR: So he vanish’d from my sight. | + | HAR: So he vanish’d from my sight. |

| − | And I pluck’d a hollow reed. | + | And I pluck’d a hollow reed. |

''(Har gets out from the cage and comes near to Heva)'' | ''(Har gets out from the cage and comes near to Heva)'' | ||

| Строка 147: | Строка 147: | ||

HAR and HEVA: And I made a rural pen, | HAR and HEVA: And I made a rural pen, | ||

And I stain’d the water clear, | And I stain’d the water clear, | ||

| − | And I wrote my happy songs | + | And I wrote my happy songs |

| − | Every child may joy to hear | + | Every child may joy to hear |

''Enter Tiriel. Mnetha, armes, stops his way.'' | ''Enter Tiriel. Mnetha, armes, stops his way.'' | ||

| Строка 159: | Строка 159: | ||

Who art thou poor blind man. that takest the name of Tiriel on thee? | Who art thou poor blind man. that takest the name of Tiriel on thee? | ||

Tiriel is king of all the West. Who art thou? [Who art thou? Who art thou?] | Tiriel is king of all the West. Who art thou? [Who art thou? Who art thou?] | ||

| − | I am Mnetha; and this is trembling like infants by my | + | I am Mnetha; and this is trembling like infants by my side — Har and Heva. |

TIR: I know Tiriel, King of the West, and there he lives in joy | TIR: I know Tiriel, King of the West, and there he lives in joy | ||

| Строка 201: | Строка 201: | ||

[those of thine own flesh, thine] own flesh? | [those of thine own flesh, thine] own flesh? | ||

| − | TIR: I am not of this | + | TIR: I am not of this region — an aged wanderer [and] once father of a race |

Far [, far] in the North; but they were wicked and were all destroyed, | Far [, far] in the North; but they were wicked and were all destroyed, | ||

I, their father, sent an outcast. I have told you all | I, their father, sent an outcast. I have told you all | ||

| Строка 576: | Строка 576: | ||

''The dance of Birds and Flowers. Dancers enter in groups of three and stand still'' | ''The dance of Birds and Flowers. Dancers enter in groups of three and stand still'' | ||

| − | ''after their «pas». After «pas» of group 12 all begin to join in a | + | ''after their «pas». After «pas» of group 12 all begin to join in a dance — one group'' |

''after another. After the first Grand Pause 4 groups go away; after the second Grand'' | ''after another. After the first Grand Pause 4 groups go away; after the second Grand'' | ||

''Pause the next 4 groups leave the stage; then the rest dancers one after another'' | ''Pause the next 4 groups leave the stage; then the rest dancers one after another'' | ||

| Строка 694: | Строка 694: | ||

END OF THE OPERA | END OF THE OPERA | ||

| − | ==SUPPLEMENT== | + | == SUPPLEMENT == |

«Tiriel» has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… | «Tiriel» has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… | ||

| Строка 722: | Строка 722: | ||

| − | Bentley: "…the tone of «Tiriel» is an extraordinarily tragic one… Tiriel shows no middle between innocence and experience, no escape for impulsive innocence. Blake’s view of the world was seldom shown darker than it is in the tortured rhetioric of «Tiriel» | + | Bentley: "…the tone of «Tiriel» is an extraordinarily tragic one… Tiriel shows no middle between innocence and experience, no escape for impulsive innocence. Blake’s view of the world was seldom shown darker than it is in the tortured rhetioric of «Tiriel» «.»<ref>Bentley, G.E. (ed.) Tiriel: facsimile and transcript of the manuscript, reproduction of the drawings and a commentary on the poem (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967)</ref> |

Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for «the lion and the patient Ox» is oppression, and under whose visionless dictatorship the arts of life, Poetry and Painting as reprmented in the idle sports of his parents Har and Heva, have not flourished. <...> | Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for «the lion and the patient Ox» is oppression, and under whose visionless dictatorship the arts of life, Poetry and Painting as reprmented in the idle sports of his parents Har and Heva, have not flourished. <...> | ||

| − | The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace, « curses his already accursed sons and calls upon them to observe their mother’s death. They bury her but declare they have rebelled against their father’s tyranny, and Tiriel wanders off through the mountains. In the „pleasant gardens of Har“ he comes upon Har and Heva as senile infants, whose imbecility illustrates the fate of those who shrink from experience—and, allegorically, the stultification of poetry and art. Tiriel is invited to help catch singing birds and hear Har „sing in the great cage“ but must wander on „because of madness & dismay“. His terrible brother Ijim seizes Tiriel and carries him back to the palace as an impostor, only to find that both father and sons are „dissemblers.“ With new curses Tiriel calls down thunder and Pestilence upon his children and finally even blights with madness his daughter Hela, his healing sense of touch, or vision, whose assistance he needs to guide him back to the pleasant valley. Tiriel is mocked and pelted with dirt and stunts as he and Hela pass the caves of Zazel, another brother. The tyrant expires at his | + | The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace, « curses his already accursed sons and calls upon them to observe their mother’s death. They bury her but declare they have rebelled against their father’s tyranny, and Tiriel wanders off through the mountains. In the „pleasant gardens of Har“ he comes upon Har and Heva as senile infants, whose imbecility illustrates the fate of those who shrink from experience—and, allegorically, the stultification of poetry and art. Tiriel is invited to help catch singing birds and hear Har „sing in the great cage“ but must wander on „because of madness & dismay“. His terrible brother Ijim seizes Tiriel and carries him back to the palace as an impostor, only to find that both father and sons are „dissemblers.“ With new curses Tiriel calls down thunder and Pestilence upon his children and finally even blights with madness his daughter Hela, his healing sense of touch, or vision, whose assistance he needs to guide him back to the pleasant valley. Tiriel is mocked and pelted with dirt and stunts as he and Hela pass the caves of Zazel, another brother. The tyrant expires at his journey’s end while explaining, like a stage villain, how his mind has been warped and how „Thy laws O Har & Tiriels wisdom end together in a curse“ (T.viii). <...> |

| − | And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»<ref>David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. | + | And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»<ref>David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. 133—135</ref> |

Frye «Tiriel, as an individual, is a man who has spent his entire life trying to domineer over others and establish a reign of terror founded on moral virtue. The result is the self-absorption, symbolized by blindness, which in the advanced age of people with such a character becomes difficult to distinguish from insanity. He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses.»<ref>Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.</ref> | Frye «Tiriel, as an individual, is a man who has spent his entire life trying to domineer over others and establish a reign of terror founded on moral virtue. The result is the self-absorption, symbolized by blindness, which in the advanced age of people with such a character becomes difficult to distinguish from insanity. He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses.»<ref>Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.</ref> | ||

Версия 14:25, 13 мая 2014

| Tiriel. Opera by Dmitri Smirnov |

An opera in three acts after a poem by William Blake Libretto

The First Act

Scene I

Scene II

Scene III

The Second Act

Scene IV

Scene V

Scene VI

The Third Act

Scene VII

Scene VIII

Scene IX

|

END OF THE OPERA

SUPPLEMENT

«Tiriel» has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… All the characters mentioned it «Tiriel» are members of one enormous family.

The wrelationships between the members of the earliest generations are the most obscure. Mnetha, a protective nurse-figure, is probably the progenitor of all the rest…

Bentley: "…the tone of «Tiriel» is an extraordinarily tragic one… Tiriel shows no middle between innocence and experience, no escape for impulsive innocence. Blake’s view of the world was seldom shown darker than it is in the tortured rhetioric of «Tiriel» «.»[6]

Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for «the lion and the patient Ox» is oppression, and under whose visionless dictatorship the arts of life, Poetry and Painting as reprmented in the idle sports of his parents Har and Heva, have not flourished. <...>

The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace, « curses his already accursed sons and calls upon them to observe their mother’s death. They bury her but declare they have rebelled against their father’s tyranny, and Tiriel wanders off through the mountains. In the „pleasant gardens of Har“ he comes upon Har and Heva as senile infants, whose imbecility illustrates the fate of those who shrink from experience—and, allegorically, the stultification of poetry and art. Tiriel is invited to help catch singing birds and hear Har „sing in the great cage“ but must wander on „because of madness & dismay“. His terrible brother Ijim seizes Tiriel and carries him back to the palace as an impostor, only to find that both father and sons are „dissemblers.“ With new curses Tiriel calls down thunder and Pestilence upon his children and finally even blights with madness his daughter Hela, his healing sense of touch, or vision, whose assistance he needs to guide him back to the pleasant valley. Tiriel is mocked and pelted with dirt and stunts as he and Hela pass the caves of Zazel, another brother. The tyrant expires at his journey’s end while explaining, like a stage villain, how his mind has been warped and how „Thy laws O Har & Tiriels wisdom end together in a curse“ (T.viii). <...>

And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»[7]

Frye «Tiriel, as an individual, is a man who has spent his entire life trying to domineer over others and establish a reign of terror founded on moral virtue. The result is the self-absorption, symbolized by blindness, which in the advanced age of people with such a character becomes difficult to distinguish from insanity. He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses.»[8]

Damon: «Tiriel is Blake’s best story (though it is somewhat pointless without the inner meaning), so Blake’s commentators have generally expressed a doubt about its being a Prophetic Book at all. This opinion has been strengthened by the fact that the symbolism of Tiriel, being early has not too much in common with the later books. But Blake imagined he had forestalled any such literal interpretation by concluding the poem with a frankly symbol section. <... > The climax bring a direct growth from the esoteric meaning, should lead the thinker back to Blake’s real thought.»[9]

Raine: «Tiriel, written about 1789, is the first of Blake’s Prophetic. Books and his first essay in myth-making. This formless, angry phantasmagoria on the theme of the death of an aged king and tyrant-father may be-indeed must be read at several levels.»[10]

In Blake’s Tiriel I see an analogy with the history of mankind, which if it isn’t abele to conquer its own vices, may come to self-destruction.

D.S.

- Notes

- ↑ “Introduction” from Songs of Innocence

- ↑ “The Tyger”. From Songs of Experience

- ↑ “A Divine Image” from “Songs of Experience” (1794).

- ↑ “The Divine Image” from “Songs of Innocence”.

- ↑ “A Cradle Song” from the Rossetty Manuscript (1794).

- ↑ Bentley, G.E. (ed.) Tiriel: facsimile and transcript of the manuscript, reproduction of the drawings and a commentary on the poem (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967)

- ↑ David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. 133—135

- ↑ Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- ↑ S. Foster Damon. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols , London, Dawsons, 1969 (reprint of the 1924 original published by Dawsons of Pall Mall).

- ↑ Kathleen Raine. Blake and Tradition. By. A. W. Mellon. Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1962