Contents • Part 1: In Russia • Part 2: In England • Blake set to music

Part 1: In Russia

I grew up in a country where English literature was considered exemplary, and it was faithfully translated into my native language by many generations of eminent translators. British or American classics were almost as popular as Russian, but of course William Shakespeare always stood in the first place and eclipsed all other authors of the world. Therefore, it is not surprising that in my early youth, when I began to write music and was looking for texts for my vocal compositions, I initially turned to setting Shakespeare’s sonnets widely known in Russian translations, by Samuil Marshak. I had only started studying English then.

One day in 1967, when by chance in a bookshop, I bought a Soviet book with an English title: In the Realm of Beauty, a collection of English-language poetry printed in English, I was struck by William Blake’s short quatrain:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand |

Vysshaya Shkola, Moscow, 1967. 320 pages, 4000 copies, price: 29 kopeyek.

It impressed me with its depth, universality—an incredible flight of the imagination, while at the same time, an amazing simplicity. I immediately felt that I had found the main thing I was looking for in art, poetry, music and in life itself. After translating it into Russian I began to translate everything from that book—there were the works of Shakespeare, Byron, Shelley, Coleridge, Keats, Burns, Edgar Allan Poe, and many other great poets, but Blake drew me in more than anybody else. Then I could not have foreseen how much this hobby would affect my music and life, causing to eventually even emigrate to the country of English bards.

Later my wife Elena Firsova, also a composer, set my first translation to music for chorus and orchestra in Augury, op. 38, 1988, one of her most monumental works, commissioned by and performed at the BBC Proms in London.

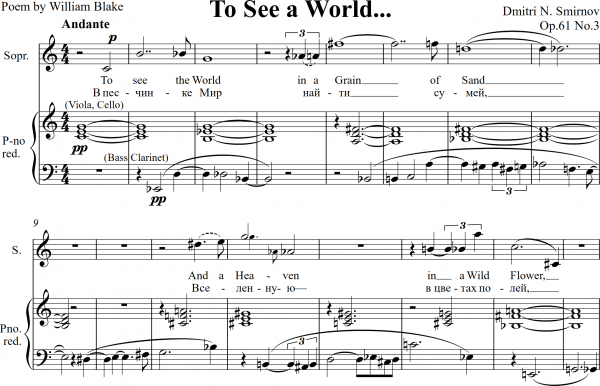

I also set to music the same text but in the original English version in my 'Three Blake Songs for voice and ensemble of 2 clarinets, viola, cello and double bass, op. 61, no. 3, 1992. A later version of this work is here:

To make it possible to perform this not only in English but also in Russian, I placed my Russian translation below the English text in the score (illus. 1).

However, the list of my works setting Blake to music begins with another piece, The Crystal Cabinet for violin and piano (or celesta), op. 27g, 1979. I was enchanted by Blake’s poem of the same title from the Pickering Manuscript that begins with:

The Maiden caught me in the Wild |

The poem tells the story of a miraculous meeting of a young man with a translucent threefold maiden “each in the other closed” with her threefold smile and threefold kiss. It gave me the simple but rather unusual structural idea to compose piece in which every bar of the accompaniment contains four triads of different notes but together embracing a complete chromatic scale. The series of these triads forms multiple and always different combinations, and on top of this harmony the melodious line of the violin, which is built of the notes suggested by the triads of the accompaniment (illus. 2).

In December of 1979 one of the most pivotal of my compositions was completed: it was The Seasons for voice, flute, viola and harp, op. 28, the setting of four Blake verses from his earliest collection, Poetical Sketches: To Spring, To Summer, To Autumn and To Winter. The cycle of them begins:

O thou, with dewy locks, who lookest down |

It was difficult to believe that these beautiful and powerful poems were written by a boy of 14. The four seasons were treated by young Blake as a complete cycle of a human life from birth to death. It was a real pleasure to set to music such wonderful poetry. This was my first serious musical appeal to Blake, which later grew into a kind of “conversion to Blake’s faith.” I’ve found that the soprano voice, together with such an exquisite instrumental combination is indeed capable of communicating some powerful drama. I extracted the pitch music material from different segments of the natural overtone scale, guided by the intuitive idea of the emotional colour of certain musical intervals that could be capable of transmitting the images of the different seasons of the year. So the intervallic material of a young ecstatic Spring was the cohesion of two minor thirds through a major second, in semitones: +3−2+3, where plus means ascending interval and minus means a descending one; a more calm and balanced Summer was identified with two major thirds connected by a minor third: +4−3+4; sad and burdened with fruits Autumn was expressed by conjugation of two minor seconds through a perfect fifth: +1+7−1; and a cold gloomy Winter was depicted with the “deadest” of intervals: the tritone linked to another tritone by means of a minor second: +6+1+6.

3. The Seasons, op. 28 no. 1. To Spring, 1979: the beginning.

This work was the most successful of my compositions of those years. After the Moscow premiere on 10th of March of 1980 performed by soprano Lydia Davydova and the ensemble under the baton of Sergei Skripka, it was repeated there in 1982 with Nikolai Korndorf as a conductor, then at the Berlin festival in 1986 with soprano Janis Harper and the Ensemble Modern conducted by Péter Eötvös , and later in England and the USA. The score and set of parts were printed by an American publisher G. Schirmer.

In May of 1980 I decided to write a symphony in four movements for a large orchestra based on my song cycle The Seasons to recreate this music by only symphonic means, without singing—like the way in which a painter turns his black and white sketch into a colourful canvas. I was also encouraged by the example of Gustav Mahler with regard to the symphonies, many of which were written on the basis of his vocal cycles. My First Symphony “The Seasons” for large symphony orchestra, op. 30, was completed in September, 1980 and dedicated to Memory of William Blake.

The premiere took place on 8th of October, 1981 in Riga. Vasily Sinaisky conducted the symphony with great inspiration and the Latvian State Orchestra played it excellently. After that, quite a few more performances followed: in Moscow , Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), Dzerzhinsk, Tanglewood (USA, Massachusetts), Daegu (South Korea), London (UK), The Hague (NL), and twice in Columbus (USA, Ohio). I have attended most of these events which was great fun. The score was printed by the Sovetsky Kompozitor Publishers, Moscow, 1988 and now is represented by Boosey and Hawkes, London.

4. The Seasons, G. Schirmer, New York, 1991: cover of the score.

5. First Symphony “The Seasons”, Sovetsky Kompozitor, Moscow, 1988: cover of the score.

In January of 1981 I wrote the song cycle called Fearful Symmetry, Six Poems by William Blake for voice and organ, op. 32, that include To Apollo—an excerpt from An Imitation of Spenser and To Muses (both are from Poetical Sketches), Morning and Day (from Rossetti Manuscript), The Sick Rose and The Tyger (from Songs of Experience). It was premiered five years later on the 10th of March, 1986, in Moscow by Lydia Davydova, soprano, and Ekaterina Prochakova, organist. Much later I created a version for voice and piano: op. 32a, 2003/2010 . The music of To Muses became also the basis of my Ballade, op. 35, 1982 for alto saxophone and piano . The music of The Tyger I rearranged a few times for a different cast of performers (see opp. 41, 61, 61a and 132). All the texture of my The Tyger is based on the idea of “fearful symmetry” and everything that appears in the lower register of the accompaniment is mirrored later in the upper one and vice versa:

6. The Tyger, op. 35 no. 6: bars 9-17. In addition to composing music I used my spare time to translate English poetry into Russian, and when I finished working on early Blake, I approached his first so called “prophetic poems”. On 18th February of 1983 I finished a translation of Tiriel, which I worked on with great enthusiasm, because I felt that this is the thing that I had been searching for so long—an excellent operatic plot with quite an actual subject: a former tyrant, removed from power and filled with the thirst for revenge, sends devastating, malicious curses to all destined to cross his path: to his sons, daughters, brothers, dear old parents, and, finally, to himself, and by this he brings death to all humanity. I read the translation to my wife Elena and she approved my idea for the opera. For a few days I worked on a libretto, and then on the 24th of February began to compose the music .

I began the Symphonic Prologue to the opera Tiriel after inventing of a specific system of repetitions of the sounds of a 12-tone series that is reminiscent of a rope twined with two identical strings. An eminent Russian musicologist Yuri Kholopov commented on this technique as follows: “The composer began his composition with a Prologue (a kind of overture), based on a series that is symmetrical in its structure... The individual mode comes from the principle of imitative interpolation of a pair of identical series leading to a regular repetition of the sound pitches ... and even to the obvious tonal colouring (quasi g-moll)”

7. Tiriel, the Symphonic Prologue to the opera, op. 41a: the beginning.

The opera Tiriel, op. 41, for soloists, chorus, dancers and full symphony orchestra was completed in January 1985 . To the text of the libretto I added also five more Blake poems: Introduction from Songs of Innocence, The Tyger from Songs of Experience, The Divine Image from Songs of Innocence, A Divine Image from Songs of Experience and A Cradle Song from Rossetti Manuscript. The latter became an epilogue of the opera: sang by the goddess Mnetha, it represents a sort of the lullaby to mankind, which had already passed away. The opera ends with the following words:

O, the cunning wiles that creep In thy little heart asleep. When thy little heart doth wake, Then the dreadful lightnings break.

From thy cheek & from thy eye O’er the youthful harvests nigh Infant wiles & infant smiles Heaven & Earth of peace beguiles.

I reused then the music of this lullaby in the second movement of my Second String Quartet, op. 42, 1985 that I dedicated to my son Philip who was just born on 8th of April .

After this I began writing my second opera The Lamentations of Thel, or just Thel, op. 45 , after another Blake’s “prophetic poem” called The Book of Thel. I liked that intimate and lyrical parable about a girl, Thel, who complains of her future death and searches for the meaning of life. When I read to Elena, my just completed translation of the poem, she said: “This is about me.” I explained that was why I decided to write an opera setting this story. I was working on this chamber opera between 1985 and 1986. This became a sort of a sequel to Tiriel, but much shorter with a smaller cast of performers and orchestra: for this it required only four singers, small chorus and ensemble of sixteen players . From the very beginning of the Prologue the music is full of the intonations of uncertainty, tormenting questions and sorrowful lamentations:

7. Thel, the Prologue to the opera, op. 45a: the beginning.

In Moscow we didn’t live in complete isolation from the world. Foreign guests: composers, musicians, publishers who increasingly visited us, were interested in our new scores, which they took with them to their homes. So, Jurgen Köchel from Hans Sikorski Publishers took the score of Tiriel to Hamburg, and David Drew from Boosey & Hawkes took the Thel to London, assuring me that it was for them. Soon I received a telegram from Köchel reporting the place and date of the future premiere of Tiriel: in Freiburg, Germany, on 28th of January 1989. It was going to be staged in the German translation by Paul Esterházy, directed by Siegfried Schoenbohm and conducted by Gerchard Markson. Eight performances of the opera were announced. This was followed by a phone call from Gerard McBurney from London, who delighted me with the news that Thel will be staged by the company Théâtre de Complicite at the Almeida theater, London, on 9, 10 and 11 June 1989, under the baton of the young and enthusiastic conductor Jeremy Arden. Soon we learned more news: in August 1989, Elena and I were invited to Tanglewood, where Oliver Knussen will conduct my First Symphony “The Seasons”. All this turned out to be an amazing gift to my 40th birthday.

9. Tiriel, Freiburg, Germany, 1989: poster. 10. Thel, London, UK, 1989: poster.

In 1987-1988 at the request of Liza Wilson, cellist and director of Chameleon Ensemble, I wrote a chamber cantata called Songs of Love and Madness, op. 49, for voice, clarinet, celesta, harp and string trio. For the text I chose four early Blake’s “Songs”: 1. How sweet I roamed… 2. My silks and fine array… 3. Love and harmony combine…, and 4. Mad Song (“The wild winds weep…). It was premiered in November, 1990 at The Huddersfield Festival by Margaret Field, soprano, Chameleon Ensemble and Andrew Ball who conducted and played celesta at the same time.

The next work written in April-June of 1988 was a piano cycle The Seven Angels of William Blake, op. 50 . There are eight movements in the cycle: 1. Prelude (Angel), 2. Lucifer, the Morning Star, 3. Molech, the executioner, 4. Elochim creating Adam, Adam creating Elochim, 5. Shaddai's Anger, 6. Pachad's Fear, 7. Jehovah appealing to Eternity, 8. Jesus the Lamb. The list of these gods and demons was taken from Blake’s epic poems Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem. I wanted to provide every of these characters with musicals portraits. Also in the work I realised my idea of the extraction of musical material from English language itself by establishing a relationship between words and melodic intervals:

11. Musical Alphabet: letter=interval, invented by © Dmitri N. Smirnov, Moscow, 1988.

For example, the name Lucifer in this system will be turned into the following pattern, the chain of musical intervals:

12. The thematic pattern for “Lucifer”.

The work was premiered on 23th of November, 1989, in Glasgow by its dedicatee a pianist Susan Bradshaw.

In 1988 I received a commission from the The Nash Ensemble for a new chamber work and I immediately thought about an astonishing watercolour Blake’s picture called Malevolence. I wanted to reflect its striking images in music. Blake himself explained the subject as “a father, taking leave of his wife and child, is watched by two fiends incarnate, with the intention that when his back is turned they will murder the mother and her infant”. I chose the combination of instruments that corresponds to the characters of the picture: the viola, flute piccolo and violin represent the “positive” characters of father, child and mother, whereas the bass clarinet and double bass represent the two “villains” of the piece; lastly, the full moon at the center of Blake’s composition that shines out “good and evil” in equal measure and is represented by the cello. I thought about the piece as some kind of a “visionary ballet” and included in it a theatrical effect: the viola player that supposes to be “a father” is leaving the stage in the middle of the performance and then is playing from the balcony. I called the piece The Moonlight Story, op. 51 . The score was finished 14th of August 1988 in Moscow and premiered on 8th June 1989 at the Almeida Theatre, London, by The Nash Ensemble and Lionel Friend, conductor. The piece became the first part of my visionary ballet Blake Pictures. Later I travelled to Philadelphia, USA, specially to see this picture in the Museum of Art. It was hidden in a special storage, but I was allowed to see and keep the picture in my hands for one hour. It was a very exceptional experience, and to my surprise a I discovered that the colours of the picture radiate light.

When I worked on my First Violin Concerto op. 54, 1990 for violin and string orchestra, I thought about images of beautiful Blake’s picture Jacob’s Dream, trying to reflect its ascending and descending images. Soon after completing of a short diptych for chorus a capella From Evening to Morning, op. 55, 1990 a set of two Blake’s poems: To the Evening Star and To Morning from the Poetical Sketches, I’ve received a commission from Michael Viner Trust to compose a new piece for a large instrumental ensemble. This gave me an opportunity to continue my visionary ballet Blake’s Picture.

13. The Seven Angels of William Blake, Kompozitor, Moscow, 1996: cover of the score.

14. Jacob’s Ladder, Boosey & Hawkes, London, 1993: cover of the score.

This was Jacob’s Ladder, for 16 players, op. 58, 1990 or Blake's Picture II – the second part of an imaginary ballet. The piece is dedicated to the memory of Michael Vyner. Here I returned back to Blake’s watercolour Jacob’s Dream, c. 1805 that depicts a giant spiral staircase descending from a shiny sun to Jacob, stretched out asleep on a rock, with winged creatures gliding up and down the ladder. I represented the ladder in this music using different scales including the overtone series and their mirror forms. The figure of Jacob is represented by a solo bassoon; the stars on the blue sky with bell-like metal percussions, harp and celesta; the angels by string and wind instruments and the words spoken by God by the bass drum. The work was premiered on 17th of April, 1991 at Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, by The London Sinfonietta, conducted by Gennady Rozhdestvensky. The score was printed by Boosey & Hawkes Publishers.

My last work written on Russian-Soviet land was A Song of Liberty op. 59, 1991 an oratorio set a complete epilogue of the same title from Blake’s prophetical phantasmagoria The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The oratorio was commissioned by the Leeds Festival Chorus for their 135th Anniversary to be performed together with C minor Mass by Mozart on 30th January, 1993 at the Leeds Town Hall, with The Leeds Festival Chorus, The BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Jerzy Maksymiuk. I used the same cast as in Mozart’s Mass: four singers, mixed chorus and orchestra, adding to it only some percussion instruments and harp. This work comprises nine movements:

I. The Eternal Female groans… Introduction II. Albion’s coast, the American meadows… Passacaglia III. Shadows of Prophecy… Soprano Aria IV. France, Spain, Rome… Canon V. The new born terror… Fantasia I VI. The fire… Chorale VII. Londoner, Jew, African… Quartet VIII. The fiery limbs… The Battle of Liberty, Fantasia II IX. Priests of the Raven… Final Chorus.

15. A Song of Liberty, op. 59, no. 7, 1991: the beginning.

The oratorio is concluded with the words: “For everything that lives is holy!”

Step by step times were changing. In the so called Perestroika period, my wife and I were able to go abroad more and more often, to attend the performances of our music. I had visited a few European countries, Poland, the United States and even South Korea. I had been to England already three times, attending the performances of The Seasons, in 1988, of The Lamentations of Thel and The Moonlight Story, in 1989, and of Songs of Love and Madness, in 1990. I attended the remarkable exhibition of Blake’s paintings and drawings, and in the British Library I was given opportunity of seeing a selection of his manuscripts and to read from the original copies of books printed and coloured by his own hand. It made me think of this country as the place I especially would like to live. At the same time the political situation in Russia began uncertain: Mikhail Gorbachov was definitely losing his power, and our colleagues and friends, composers and musicians were looking for any possibilities to abandon the “sinking ship”.

In January, 1991 in Moscow I suddenly received a postcard from Kathleen Raine, whom I had never met before, but whose wonderful books about Blake I loved very much. She wrote to me that she had been very surprised to learn from some of her friends that in Russia there is a composer who is crazy about Blake, as she is. And she asked me when I was next in London to come to her place at 47 Paulton Square for a cup of tea. I answered that I was happy to accept her invitation and invited her to come to the performance of my Jacob’s Ladder in April at the South Bank Festival. Very soon I received her letter where she wrote: “It was with great surprise and pleasure that I received your letter about Blake and your love for him and your music based on his great inner worlds. I will make every effort to come to the performance of ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ on April 17th. Of all Blake’s paintings it is probably the one I love best... It is wonderful to think that you have made Blake renowned in Russia at this time”.

The Southbank Festival sent the invitation to us in September, 1990 long time in advance and we began to prepare documents for obtaining the visas. To our great surprise we received also something that we never received before: the permission to take our small children together with us: Philip was 6 and Alissa only 4 then. This suddenly opened an incredible opportunity for us to try to begin a new life in a completely different part of the world, and 13th of April, 1991 we arrived to Great Britain, where we have lived ever since.

16. The letter from Kathleen Raine, 8th February 1991.