Tiriel (libretto): различия между версиями

| Строка 693: | Строка 693: | ||

== SUPPLEMENT == | == SUPPLEMENT == | ||

| − | Bentley: "Tiriel has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… | + | Bentley: "''Tiriel'' has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… |

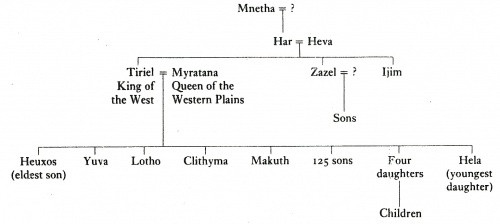

| − | All the characters mentioned | + | All the characters mentioned in ''Tiriel'' are members of one enormous family. <...> |

[Family relations] | [Family relations] | ||

| Строка 700: | Строка 700: | ||

[[Файл:Tiriel relations- scheme.jpg|500px|center]] | [[Файл:Tiriel relations- scheme.jpg|500px|center]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The relationships between the members of the earliest generations are the most obscure. Mnetha, a protective nurse-figure, is probably the progenitor of all the rest. <...> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The relationships between the members of the earliest generations are the most obscure. Mnetha, a protective nurse-figure, is probably the progenitor of all the | ||

[Travelling scheme of Tiriel] | [Travelling scheme of Tiriel] | ||

| Строка 725: | Строка 707: | ||

[[Файл:Tiriel-travels.jpg|500px|center]] | [[Файл:Tiriel-travels.jpg|500px|center]] | ||

| + | …the tone of ''Tiriel'' is an extraordinarily tragic one… ''Tiriel'' shows no middle between innocence and experience, no escape for impulsive innocence. Blake’s view of the world was seldom shown darker than it is in the tortured rhetioric of ''Tiriel''."<ref>Bentley, G.E. (ed.) ''Tiriel:'' facsimile and transcript of the manuscript, reproduction of the drawings and a commentary on the poem (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967)</ref> | ||

| − | + | Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for 'the lion and the patient Ox' is oppression, and under whose visionless dictatorship the arts of life, Poetry and Painting as reprmented in the idle sports of his parents Har and Heva, have not flourished. <...> | |

| − | |||

| − | Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for | ||

| − | The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace, | + | The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace", curses his already accursed sons and calls upon them to observe their mother’s death. They bury her but declare they have rebelled against their father’s tyranny, and Tiriel wanders off through the mountains. In the „pleasant gardens of Har“ he comes upon Har and Heva as senile infants, whose imbecility illustrates the fate of those who shrink from experience—and, allegorically, the stultification of poetry and art. Tiriel is invited to help catch singing birds and hear Har „sing in the great cage“ but must wander on „because of madness & dismay“. His terrible brother Ijim seizes Tiriel and carries him back to the palace as an impostor, only to find that both father and sons are „dissemblers.“ With new curses Tiriel calls down thunder and Pestilence upon his children and finally even blights with madness his daughter Hela, his healing sense of touch, or vision, whose assistance he needs to guide him back to the pleasant valley. Tiriel is mocked and pelted with dirt and stunts as he and Hela pass the caves of Zazel, another brother. The tyrant expires at his journey’s end while explaining, like a stage villain, how his mind has been warped and how „Thy laws O Har & Tiriels wisdom end together in a curse“ (T.viii). <...> |

And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»<ref>David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. 133—135</ref> | And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»<ref>David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. 133—135</ref> | ||

| − | Frye | + | Frye "Tiriel, as an individual, is a man who has spent his entire life trying to domineer over others and establish a reign of terror founded on moral virtue. The result is the self-absorption, symbolized by blindness, which in the advanced age of people with such a character becomes difficult to distinguish from insanity. He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses."<ref>Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.</ref> |

| − | Damon: | + | Damon: "''Tiriel'' is Blake’s best story (though it is somewhat pointless without the inner meaning), so Blake’s commentators have generally expressed a doubt about its being a Prophetic Book at all. This opinion has been strengthened by the fact that the symbolism of ''Tiriel'', being early has not too much in common with the later books. But Blake imagined he had forestalled any such literal interpretation by concluding the poem with a frankly symbol section. <... > The climax bring a direct growth from the esoteric meaning, should lead the thinker back to Blake’s real thought."<ref>S. Foster Damon. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols , London, Dawsons, 1969 (reprint of the 1924 original published by Dawsons of Pall Mall). </ref> |

| − | Raine: | + | Raine: "''Tiriel'', written about 1789, is the first of Blake’s Prophetic. Books and his first essay in myth-making. This formless, angry phantasmagoria on the theme of the death of an aged king and tyrant-father may be-indeed must be read at several levels."<ref>Kathleen Raine. Blake and Tradition. By. A. W. Mellon. Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1962</ref> |

| − | In Blake’s Tiriel I see an analogy with the history of mankind, which if it isn’t abele to conquer its own vices, may come to self-destruction. | + | In Blake’s ''Tiriel'' I see an analogy with the history of mankind, which if it isn’t abele to conquer its own vices, may come to self-destruction. |

{{right|''[[D. Smirnov-Sadovsky|DS]] 1988''}} | {{right|''[[D. Smirnov-Sadovsky|DS]] 1988''}} | ||

Версия 19:40, 13 мая 2014

| Tiriel. Opera by Dmitri Smirnov |

An opera in three acts after a poem by William Blake Libretto

The First Act

Scene I

Scene II

Scene III

The Second Act

Scene IV

Scene V

Scene VI

The Third Act

Scene VII

Scene VIII

Scene IX

|

SUPPLEMENT

Bentley: "Tiriel has always proved a puzzle to commentators on Blake… All the characters mentioned in Tiriel are members of one enormous family. <...>

[Family relations]

The relationships between the members of the earliest generations are the most obscure. Mnetha, a protective nurse-figure, is probably the progenitor of all the rest. <...>

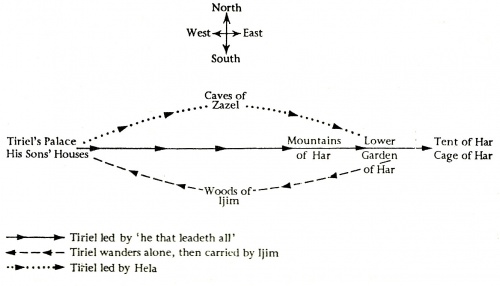

[Travelling scheme of Tiriel]

…the tone of Tiriel is an extraordinarily tragic one… Tiriel shows no middle between innocence and experience, no escape for impulsive innocence. Blake’s view of the world was seldom shown darker than it is in the tortured rhetioric of Tiriel."[6]

Erdman: "The evils of inequality and the fallacy of attempting to live for oneself alone are elaborately demonstrated in Tiriel, a murky parable of the decline and fall of a tyrant prince who leams to his sorrow that one law for 'the lion and the patient Ox' is oppression, and under whose visionless dictatorship the arts of life, Poetry and Painting as reprmented in the idle sports of his parents Har and Heva, have not flourished. <...>

The blind aged King, standing before his "beautiful palace", curses his already accursed sons and calls upon them to observe their mother’s death. They bury her but declare they have rebelled against their father’s tyranny, and Tiriel wanders off through the mountains. In the „pleasant gardens of Har“ he comes upon Har and Heva as senile infants, whose imbecility illustrates the fate of those who shrink from experience—and, allegorically, the stultification of poetry and art. Tiriel is invited to help catch singing birds and hear Har „sing in the great cage“ but must wander on „because of madness & dismay“. His terrible brother Ijim seizes Tiriel and carries him back to the palace as an impostor, only to find that both father and sons are „dissemblers.“ With new curses Tiriel calls down thunder and Pestilence upon his children and finally even blights with madness his daughter Hela, his healing sense of touch, or vision, whose assistance he needs to guide him back to the pleasant valley. Tiriel is mocked and pelted with dirt and stunts as he and Hela pass the caves of Zazel, another brother. The tyrant expires at his journey’s end while explaining, like a stage villain, how his mind has been warped and how „Thy laws O Har & Tiriels wisdom end together in a curse“ (T.viii). <...>

And many details suggest that he was drawing upon the living example of King George—as well as the literary example of King Lear—when he composed this story of a king and father gone amok, pulling down the temple like a blind Samson (but no deliverer), cursing sons and daughters, and storming about the wilderness bemoaning his loss of a western empire.»[7]

Frye "Tiriel, as an individual, is a man who has spent his entire life trying to domineer over others and establish a reign of terror founded on moral virtue. The result is the self-absorption, symbolized by blindness, which in the advanced age of people with such a character becomes difficult to distinguish from insanity. He expects and loudly demands gratitude and reverence from his children because he wants to be worshipped as a god, and when his demands are answered by contempt he responds with a steady outpouring of curses."[8]

Damon: "Tiriel is Blake’s best story (though it is somewhat pointless without the inner meaning), so Blake’s commentators have generally expressed a doubt about its being a Prophetic Book at all. This opinion has been strengthened by the fact that the symbolism of Tiriel, being early has not too much in common with the later books. But Blake imagined he had forestalled any such literal interpretation by concluding the poem with a frankly symbol section. <... > The climax bring a direct growth from the esoteric meaning, should lead the thinker back to Blake’s real thought."[9]

Raine: "Tiriel, written about 1789, is the first of Blake’s Prophetic. Books and his first essay in myth-making. This formless, angry phantasmagoria on the theme of the death of an aged king and tyrant-father may be-indeed must be read at several levels."[10]

In Blake’s Tiriel I see an analogy with the history of mankind, which if it isn’t abele to conquer its own vices, may come to self-destruction.

- Notes

- ↑ “Introduction” from Songs of Innocence

- ↑ “The Tyger”. From Songs of Experience

- ↑ “A Divine Image” from “Songs of Experience” (1794).

- ↑ “The Divine Image” from “Songs of Innocence”.

- ↑ “A Cradle Song” from the Rossetty Manuscript (1794).

- ↑ Bentley, G.E. (ed.) Tiriel: facsimile and transcript of the manuscript, reproduction of the drawings and a commentary on the poem (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967)

- ↑ David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977, p. 133—135

- ↑ Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- ↑ S. Foster Damon. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols , London, Dawsons, 1969 (reprint of the 1924 original published by Dawsons of Pall Mall).

- ↑ Kathleen Raine. Blake and Tradition. By. A. W. Mellon. Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1962